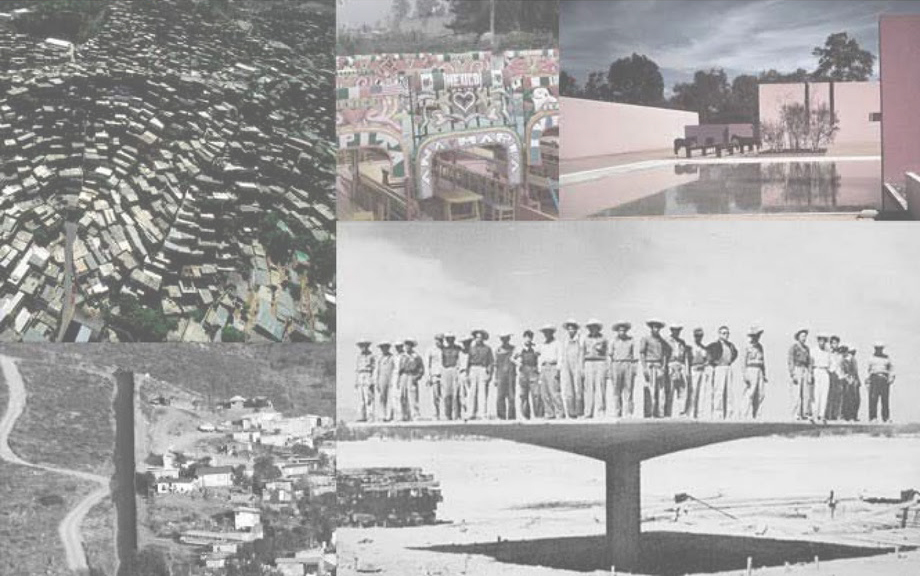

Water Infrastructure: collecting water and desert rain; creating a dam and fence.

"The Border Wall Project tries to prepare the world post the existence of the 'line'..... in hopes of creating a conceptual dematerialization." -- Ron Rael

Rascuache, a Spanish word meaning: poor, penniless, tacky, usually of/or relating to bad taste. A word used by Ron Rael to describe the typical aesthetics of homes, stores, and impoverished communities in Mexico; especially in border towns. Despite this negative connotation, the word observes a limited architecture that can potentially become something better; an improvised architecture that quickly ameliorates a problem on-hand.

Rael introduced the BorderWall presentation with a very particular project: an installed sculpture that creates a mirage in the middle of the desert of Marfa, Texas (image below). Prada Marfa (2005) resembles a store-front, but it is only a facade that tries to "converge between the convergent and nonconvergent" as Rael describes. What goes with what, what doesn't, and where? The facade becomes a criticism of what Prada might be, "luxury capitalism."

Ironically, the most basic building materials, adobe and mud-bricks were used for this construction and made reference to the West Texas desert-site and juxtaposed the usual glamor of Prada. And a photograph of glass, or "non-glass" was used to mimic the transparency of real glass. "This becomes a symbol of excess in the middle of nowhere...ridiculousness in the middle of nowhere...Prada Marfa makes reference to wealth... famous people's houses located in the middle of nowhere...the real versus the unreal," states Rael.

By artists Elmgreen and Dragset; Assistance of Ron Rael and Virginia San Fratello.

Prada Marfa is popularly described as "quirky," yet it is best described as satirical. His statements criticize the narrow/limited perspectives on how we approach social or political issues. Similarly, Rael describes the US-Mexico Border Wall spanning through 700 miles and costing 49 billion dollars per year on maintenance and security, as a ridiculous object in the middle of nowhere. This proposal addresses issues of National Security and provides solutions for water conservation, renewable energy, and social integration. "As a designer, I'm not protesting for, or against the wall..just embracing the wall for what it is, " Ron describes the wall as a migration inhibitor for animals, students, families that cross the border on a daily basis.

Social Infrastructure: Urban Park creates ramps for walking or sports. Various hot spots promote social integration, like libraries or theaters---allowing people to be on either sides of the wall.

Rael described the various design proposals, starting with the Water Infrastructure (most-top image). Located in the city of Nogales, this fence would act as a dam and actually block people from moving in-and-out a great portion of the wall. Along the fence, various programs would encourage gatherings. For instance, theater spaces for binational sports or musical performances, or even linear water parks. Further, this water-solution-wall would include a waste water treatment plant to create a linear path dealing with chemical runoff, including: flow of sewage, heavy materials, and diseases. The same water would integrate solar energy, or photovoltaic panels to create shelters with running water for both families and animals.

"What I seek to convey is the historic truth that the United States as a nation has at all times maintained clear, definite opposition, to any attempt to lock us in behind an ancient Chinese wall while the procession of civilization went past. Today, thinking of our children and of their children, we oppose enforced isolation for ourselves or for any other part of the Americas."

Ron Rael concluded his lecture with the above quote by Franklin D. Roosevelt's 1941 State of the Union Address. Ron addressed the need to look beyond the wall--to not take political sides, but instead embrace the wall and understand the ridiculousness of his project itself, and the existence of a wall in the middle of nowhere.

Burrito Wall: Creates a comical/satirical solution allowing those on the Mexico-side to make and sell local food for people on the US-side.

Similar approaches (not pictured) include: The Communion Wall- allowing people to engage in mass or Catholic ritual of holy communion; The Xylophone Wall- allowing people to play music on both sides of the wall.

All approaches try to bring out the most positive aspects of the current issues by increasing social interaction and making the wall less visible.

More about the Border Wall Project and Ron Rael ::: www.rael-sanfratello.com

Ron Rael is an architect, author, and Assistant Professor at the University of California, Berkeley. He received his Master's of Architecture at Columbia and also taught at the University of Arizona. Rael's research examines the convergence of digital, industrial, and non industrial approaches to making architecture.

He is the author of "Earth Architecture," examining the contemporary history of the oldest and most widely used building material on the planet-- dirt. Our conversation with CASA discusses different design proposals that examine different strategies for the US-Mexico border wall.